20 Microservices, 1 Rails Monolith, and Why Elixir Would Have Simplified Everything

I once worked on a mobility platform—ride-hailing and food delivery. The architecture looked impressive from the outside: 20 microservices, 10 of them in Go, a central Rails monolith, Redis everywhere, RabbitMQ for inter-service communication, and a team spending more time orchestrating infrastructure than building features.

Then I discovered Elixir. And I realized we’d been overcomplicating things.

The “State of the Art” Architecture

Here’s what we had built:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Load Balancer │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌─────────────────────┼─────────────────────┐

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐

│ Rails API │ │ Rails API │ │ Rails API │

│ (Puma x16) │ │ (Puma x16) │ │ (Puma x16) │

└───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘

│ │ │

└─────────────────────┼─────────────────────┘

│

┌─────────────────────┼─────────────────────┐

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐ ┌───────────────┐

│ Redis │ │ RabbitMQ │ │ PostgreSQL │

│ (sessions, │ │ (job queue, │ │ (data) │

│ cache) │ │ pub/sub) │ │ │

└───────────────┘ └───────────────┘ └───────────────┘

│ │

│ ┌───────────────┴───────────────┐

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

┌───────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────┐

│ Go Services │ │ Go Services │

│ (concurrency, │ ... │ (workers, │

│ real-time) │ │ processing) │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

x10 Go servicesWhy Go for 10 services? Because Rails couldn’t handle concurrency well. Goroutines and channels seemed like the obvious solution for anything requiring parallelism.

Why Redis? Because Rails doesn’t have native distributed caching.

Why RabbitMQ? Because we needed asynchronous communication between services.

Why Sidekiq? Because Rails can’t do background jobs natively.

The Revelation: “The Soul of Erlang and Elixir”

One day, I stumbled upon Saša Jurić’s talk “The Soul of Erlang and Elixir”. And everything clicked.

Saša demonstrates something simple yet profound: the BEAM provides everything you’d go looking for elsewhere.

Redis? ETS.

We used Redis for caching, sessions, counters, distributed locks.

# Rails + Redis

Rails.cache.fetch("user:#{id}", expires_in: 1.hour) do

User.find(id).to_json

endThe BEAM has ETS (Erlang Term Storage), an in-memory database built into the runtime:

# Elixir + native ETS

:ets.new(:users_cache, [:set, :public, :named_table])

:ets.insert(:users_cache, {user_id, user_data})

:ets.lookup(:users_cache, user_id)No external server. No network latency. No additional point of failure.

For more advanced caching with automatic expiration, Cachex or ConCache do the job:

# Cachex - cache with TTL, stats, warmers

Cachex.put(:my_cache, "user:#{id}", user_data, ttl: :timer.hours(1))

Cachex.get(:my_cache, "user:#{id}")Puma? Cowboy/Bandit + Phoenix.

Rails with Puma: a limited worker pool, each request blocks a worker.

# config/puma.rb

workers 4

threads 5, 16

# Max: 4 * 16 = 64 simultaneous requests per serverPhoenix with Cowboy (or Bandit): each connection is a lightweight BEAM process (~2KB).

# Phoenix can handle millions of connections

# No pool configuration needed

# Each request = 1 isolated processWhatsApp handles 2 million connections per server with the BEAM. Discord too. Pinterest too.

Go for Concurrency? BEAM Processes.

We wrote 10 services in Go because we needed concurrency. Goroutines and channels seemed perfect.

// Go: channels for communication

func worker(jobs <-chan Job, results chan<- Result) {

for job := range jobs {

results <- process(job)

}

}

func main() {

jobs := make(chan Job, 100)

results := make(chan Result, 100)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go worker(jobs, results)

}

}But the BEAM has been doing this since 1986:

# Elixir: same pattern, built into the language

defmodule Worker do

def start_link do

Task.async(fn -> process_jobs() end)

end

def process_jobs do

receive do

{:job, data} ->

result = process(data)

send(caller, {:result, result})

process_jobs()

end

end

end

# Or more simply with Task.async_stream

jobs

|> Task.async_stream(&process/1, max_concurrency: 10)

|> Enum.to_list()The crucial difference? BEAM processes are supervised. If a worker crashes, the supervisor restarts it. In Go, you handle that yourself.

RabbitMQ? Phoenix.PubSub + GenServer.

For inter-service communication, we had RabbitMQ:

# Rails + Bunny (RabbitMQ)

connection = Bunny.new

connection.start

channel = connection.create_channel

queue = channel.queue("events")

queue.subscribe do |info, properties, body|

process_event(JSON.parse(body))

endPhoenix has PubSub built in:

# Phoenix PubSub - natively distributed

Phoenix.PubSub.subscribe(MyApp.PubSub, "events")

Phoenix.PubSub.broadcast(MyApp.PubSub, "events", {:new_event, data})

# In a GenServer or LiveView

def handle_info({:new_event, data}, state) do

# Process the event

{:noreply, state}

endAnd if you really need persistent message queuing? Broadway with SQS or RabbitMQ. But for 90% of cases, PubSub is enough.

Sidekiq? GenServer + Task.

Background jobs in Rails = Sidekiq + Redis:

# Rails + Sidekiq

class HardWorker

include Sidekiq::Worker

def perform(user_id)

# Long-running task

end

end

HardWorker.perform_async(user_id)In Elixir, processes do this natively:

# Elixir - no external dependency

Task.start(fn ->

# Long-running task in a separate process

process_user(user_id)

end)

# Or with supervision for resilience

Task.Supervisor.start_child(MyApp.TaskSupervisor, fn ->

process_user(user_id)

end)For persistent jobs with retry, there’s Oban:

# Oban - database-backed persistent jobs

defmodule MyApp.Workers.EmailWorker do

use Oban.Worker

@impl Oban.Worker

def perform(%Oban.Job{args: %{"user_id" => user_id}}) do

send_email(user_id)

:ok

end

end

%{user_id: 123}

|> MyApp.Workers.EmailWorker.new()

|> Oban.insert()What We Could Have Had

With Elixir, our architecture would have become:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Load Balancer │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Phoenix Application │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Web │ │ Channels │ │ LiveView │ │

│ │ (API) │ │ (WebSocket)│ │ (Real-time)│ │

│ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ ETS │ │ PubSub │ │ GenServers │ │

│ │ (Cache) │ │ (Events) │ │ (Workers) │ │

│ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Oban │ │ Supervisors │ │

│ │ (Jobs) │ │ (Recovery) │ │

│ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌───────────────┐

│ PostgreSQL │

└───────────────┘One single deployment. No Redis. No RabbitMQ. No 10 Go services to maintain.

The Hidden Cost of Microservices

What we never measure:

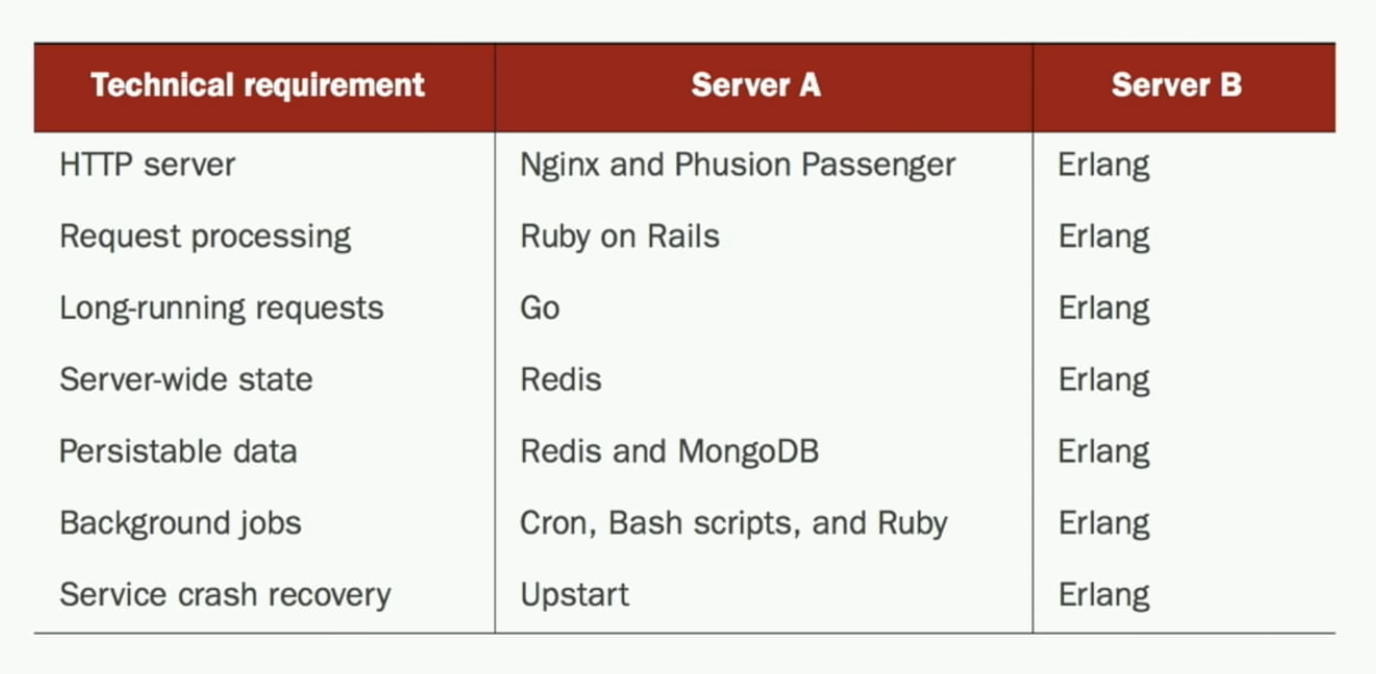

| Element | Our stack | Elixir |

|---|---|---|

| Services to deploy | 21 | 1 |

| Databases | PostgreSQL + Redis | PostgreSQL |

| Message brokers | RabbitMQ | None |

| Languages to maintain | Ruby + Go | Elixir |

| Points of failure | ~25 | ~3 |

| Cross-service debugging time | Hours | Minutes |

| Monthly infra cost | $$$$$ | $$ |

Microservices make sense when teams are large and independent. For a team of 5-10 devs, it’s often accidental complexity.

The Beauty of the BEAM Approach

Saša Jurić summarizes it perfectly: the BEAM isn’t just a VM, it’s an operating system for concurrent applications.

Error Isolation

Each process is isolated. A crash doesn’t affect others:

# A process that crashes

spawn(fn ->

raise "Boom!" # This process dies

end)

# Others continue as if nothing happened

spawn(fn ->

:timer.sleep(1000)

IO.puts("I'm still here")

end)Supervision Trees

Supervisors automatically restart crashed processes:

defmodule MyApp.Application do

use Application

def start(_type, _args) do

children = [

{MyApp.Cache, []},

{MyApp.WorkerPool, []},

MyAppWeb.Endpoint

]

# If a child crashes, it gets restarted

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: MyApp.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

endNative Distribution

Connecting multiple BEAM nodes:

# Node A

Node.connect(:"node_b@server2")

# Call a function on Node B

:rpc.call(:"node_b@server2", MyModule, :my_function, [args])

# Or send a message to a remote process

send({:my_process, :"node_b@server2"}, :hello)No special configuration. No external service discovery. It just works.

What I Would Do Differently

If I had to rebuild that platform today:

- A Phoenix monolith to start, not microservices

- LiveView for the real-time dashboard instead of a React SPA

- GenServers for workers instead of 10 Go services

- ETS/Cachex instead of Redis

- Phoenix.PubSub instead of RabbitMQ

- Oban for persistent jobs

The result? A more productive team, less ops, and probably better performance.

The Myth of “Rails for CRUD, Go for Performance”

This separation is artificial. It comes from Ruby’s limitations, not from thoughtful architectural choices.

Elixir does both:

- Developer productivity: elegant syntax, excellent tooling, Phoenix as productive as Rails

- Performance: native concurrency, low latency, trivial horizontal scaling

You no longer have to choose.

Wrapping Up

I don’t regret that experience. It taught me what a distributed architecture really costs.

But today, when I start a new project, the question is no longer “which language for which service”. It’s: “do I really need multiple services?”

The answer is often no. And Elixir lets me build something simple, performant, and resilient.

As Saša Jurić puts it: the BEAM is a complete system. Why go looking elsewhere for what you already have at hand?

Resources

- The Soul of Erlang and Elixir - Saša Jurić

- Phoenix Framework

- Oban - Background Jobs

- Cachex - Caching

- Broadway - Data Processing

Got a complex architecture you’d like to simplify? Let’s talk — we’ve been there.